When Your Health Becomes Someone Else’s Business Model

How the Attention Economy is now coming for your body.

At 6:12 a.m., my wrist buzzed to tell me I had slept badly.

I was standing in the kitchen, bare feet on cold tile, listening to the coffee maker click and hiss. My joints were quiet. My head was clear in the way that makes the air feel sharp and easy to track. Breath low and unforced. The kind of morning you notice precisely because it is rare.

The watch gave a short vibration. Low recovery. I reached for my phone to get the details.

That’s when it started.

First, a swipe past the notifications that had piled up overnight. A live stream I’d wanted to catch, missed just before I went to sleep. Twenty-something alerts from various apps, most of them irrelevant, a few with just enough weight to make me pause. Then a work message that pulled me sideways: a priority ticket that needed confirming, a quick check to make sure staff had it handled. That became a ten-minute detour I hadn’t planned on taking before coffee.

By the time I remembered why I’d picked up the phone in the first place, the quiet in my body had already shifted. The morning that had felt grounded was now running a background hum of small activations.

I finally opened the health app.

Red readiness score. Sleep “below baseline.” Suggested prompts: lower training load, more wind-down time, less late screen exposure. A plausible, generic story about a morning I was not actually having.

Or maybe I was having it now.

The morning had started with my body feeling good. Fifteen minutes later, I wasn’t sure anymore. Not because the data had revealed something. Because the process of checking had already changed the state I was trying to measure.

This is the atmosphere we’re breathing now.

What used to be grounding morning rituals, the slow entry into a day, have been replaced by this: a drip feed of nervous system hits before your feet are warm. Notifications triggering micro-doses of vigilance. Algorithms personalizing your dopamine supply. The health metrics riding on top of a stack that’s already primed you to feel behind, reactive, slightly urgent.

And AI automation is delivering all of it faster, more effectively, and more precisely targeted than ever.

Your version of this scene might not involve my kitchen or my watch.

Maybe it happens at lunch, in a parked car outside work, when you open your phone “for a second” and a reel tells you that your symptoms sound exactly like adrenal collapse.

Maybe it happens at midnight, blue light pooling across the sheets, while a podcast host lists “five signs your doctor is missing the real root cause,” and four of them sound uncomfortably familiar.

Your body says one thing. The screen, or the device, tells another. The outside story arrives louder, or first.

Somewhere in that gap, a quiet transfer takes place. The question is no longer “How do I feel?” but “Which version of reality gets to count?”

That small shift is what this essay is about.

Not a rant about phones. Not a call to throw away your devices. Not a campaign for one diet over another. Not an anti-AI manifesto.

This is a field report on what happens to a person’s ability to think for themselves in an environment where their health, their curiosity, and their uncertainty are all very profitable.

And what changes when you notice that.

We’ve Been Here Before

If you grew up in the 70s or 80s, you remember a different kind of health script.

Cereal commercials sounded like public service announcements. Athletes on orange boxes promised greatness if you ate toasted flakes with added vitamins. Margarine was a heart-saving upgrade from butter. The food pyramid was settled fact. Low-fat everything.

A lot of us internalized that without much analysis. Fat was dangerous. Cholesterol was something to fear. Six plus servings of whole grains were essential. Sugar was fine if you “burned it off.” TV carried authority because everyone we knew watched the same shows and saw the same ads. It was the air we breathed.

Later, some of us ended up in doctors’ offices with symptoms that didn’t fit the script. In my case, years of gut pain that eventually became a Crohn’s diagnosis. Early on, when I started to notice how much certain foods changed my symptoms, I tried to talk about it.

The response was polite and consistent. Diet might “play a role,” but the real game was medication and disease management. A gentle steering back to the standard of care.

We were already being trained to treat external scripts as more real than the feedback coming from our own bodies. We trusted the guidelines over the patterns we saw in our own data, because the guidelines arrived through official channels and our data arrived as pain and fatigue and bathroom trips.

Back then, at least, everyone saw the same thing. The commercials may have been wrong, the advice incomplete, but it was shared. The story was one story.

That part has changed.

Tiny Betrayals of Your Own Signals

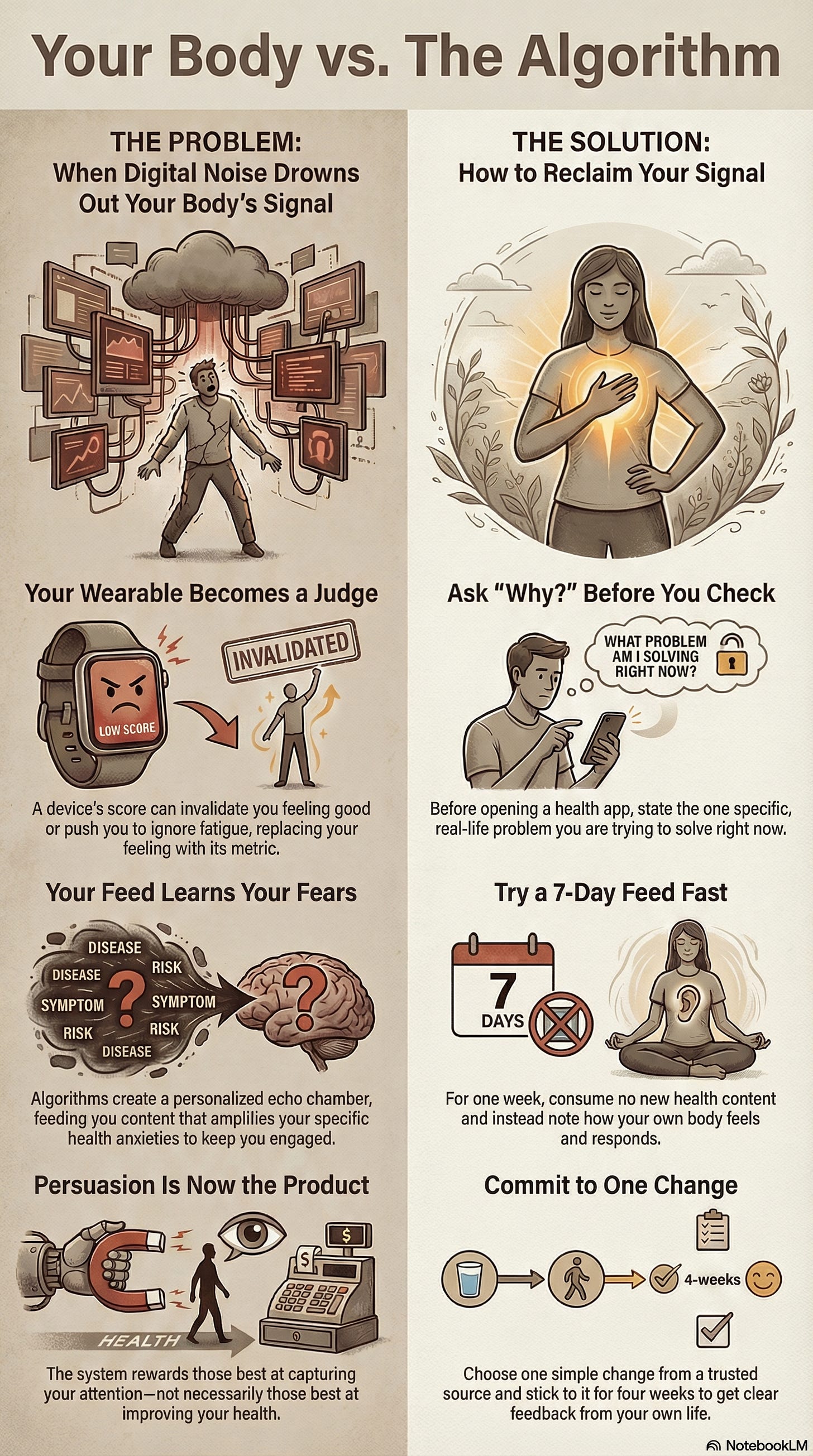

The first shift is usually small.

A device tells you to take it easy on a day you feel fine. Or it tells you you’re “primed” when you already know you’re cooked.

Maybe you obey the red score and cancel a walk, even though the idea of moving your body felt good.

Maybe you ignore the exhaustion and push because the app says “go.”

In my case, the morning in the kitchen was not the first time this happened. There were other days when I changed a workout or altered a schedule based less on what I felt and more on a number on the screen.

It doesn’t feel like much at the time. One override. One deference. You’re being “evidence-based.” You’re trying not to fool yourself. You tell yourself your body is subjective and the metric is objective, and objectivity is what responsible adults aim for.

But it’s worth asking:

If you contradict a signal from your own nervous system fifty times in favor of an external score, what happens to that signal?

It doesn’t disappear. It just stops being trusted.

That’s where the story we’re in now begins. Not with dramatic tech, but with small, repeated decisions to give something outside us the last word about our inner experience.

From there, the surrounding environment takes over.

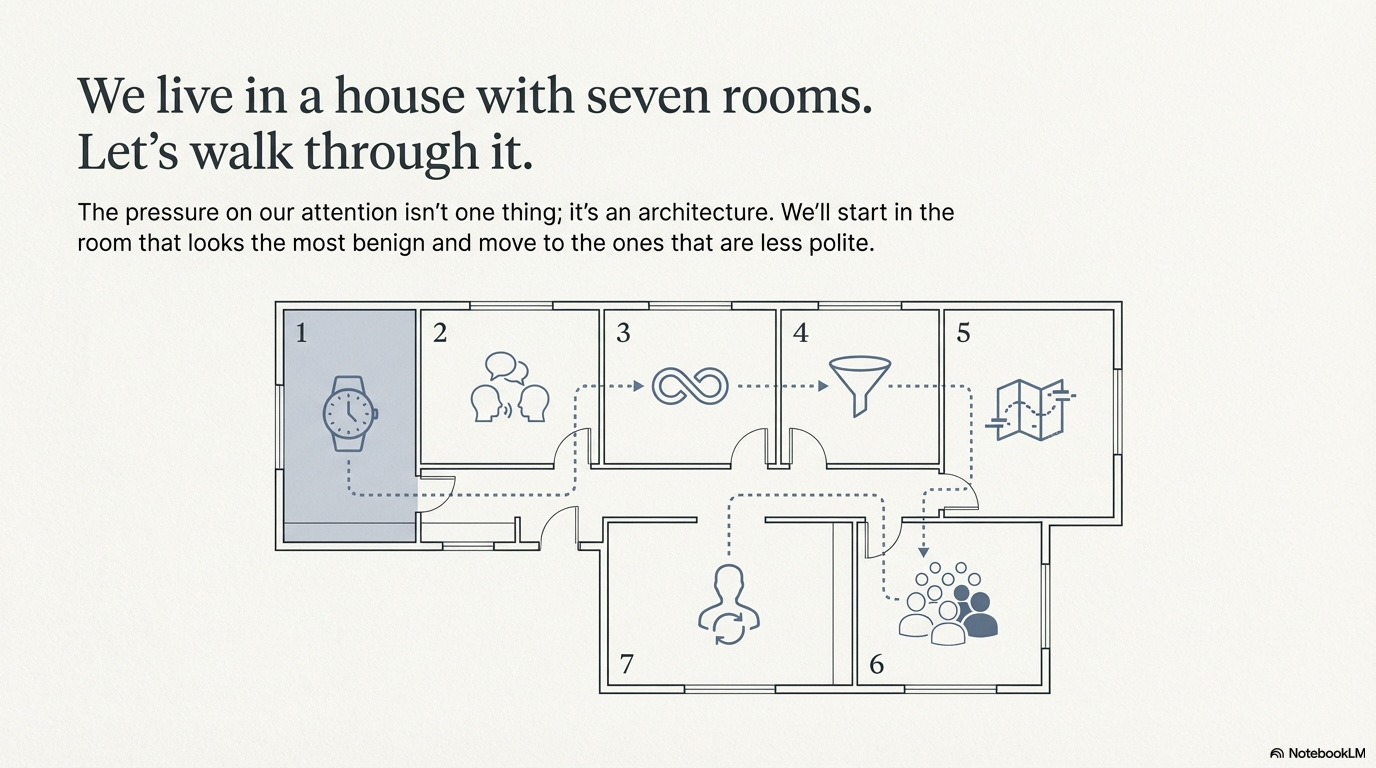

Room One: When Tools Start Talking Like Judges

Let’s walk through the house we’re in.

We’ll start in the room that looks the most benign.

If you wear a ring, watch, band, or use health dashboards, you already know the basic pattern. You wake up and check a score before you check in with yourself. You flip your wrist or your phone, see green, yellow, or red, and only then ask, “How do I feel?”

At first, tools like this are genuinely helpful.

They show patterns you couldn’t easily see on your own. Heart rate variability trends. Sleep stages. Recovery scores. They give you language and graphs for what used to be fuzzy impressions.

Over time, something can tilt.

The tool that started as a mirror becomes a referee.

A “good” score means your sense of having a rough morning feels like weakness or dramatization. A “bad” score means your sense of having a surprisingly good morning feels naïve. The number migrates from one input among many to the deciding vote.

From the company’s point of view, this is success. The business survives when the device stays on your wrist and the app opens often. Anything that increases your feeling of needing the metric is good for retention. Their job is to keep the mirror interesting. Your job, from their perspective, is to keep looking.

Neither role is evil. It’s just worth seeing the arrangement clearly.

If tomorrow your device fell in the sink and never turned back on, how much real capability would you lose?

Would you immediately lose the ability to tell whether to push a workout, eat more, sleep earlier, say no to a request?

Or would you discover that you had been deferring those calls to something that was never actually in your body to begin with?

In this room, the pressure on your attention is subtle. The tool asks to be consulted first. Other rooms are less polite.

Room Two: Experts Who Can’t All Be Right at Once

In my own case, there were long stretches where the stack of lab reports on my desk was thicker than the stack of books I was reading for pleasure. Stool tests. Hormone panels. Nutrient reports. Immune markers.

None of these are bad. Used well, they can shorten the time between uncertainty and insight.

The interesting part is what happens when you lay the same data in front of different people.

One practitioner sees stress physiology and circadian disruption. The plan emphasizes sleep, light, and nervous system work.

Another sees stealth infection and immune burden. The plan emphasizes antimicrobials, gut support, and detox.

Another sees unprocessed emotional shock, chronic vigilance, and relational strain as the central pattern. The plan emphasizes nervous system safety, boundaries, and grief.

All of these people are intelligent, sincere, and not obviously wrong.

You may have your own version: the conventional doctor, the functional MD, the nutritionist, the trauma-informed therapist, the podcast MD. Each offering a framework that sounds complete while highlighting a different slice of your life.

There are predictable ways this plays out.

You pick one voice, decide “this is my person,” and ignore the rest.

You switch when relief plateaus, hoping the next framework finally explains everything.

You try to merge them, building a protocol that no actual human with work, family, and a nervous system can live for more than a week.

In every version, interpretation multiplies faster than experiments.

The risk is not that any given expert is malicious. The risk is that your own pattern recognition becomes the quietest voice in the room.

If you look back over the last few years, how many changes in your health life came from an external interpretation, and how many came from something you discovered directly, through your own small trials?

The answer to that says something about whose story you’ve been living.

Room Three: Feeds That Learn Your Fears

Now we step into a louder room.

There is a particular kind of evening many of us know now.

You sit down meaning to “do some research.”

The intent is practical. Figure out what to do about fatigue. Understand what is happening with hormones. See if anyone else has put together the same weird cluster of symptoms you have.

You type something like “bloating won’t go away” or “can’t focus, tired all the time” into a search bar.

At first, you get what you expect. Big health sites. Hospital pages. A few sponsored links with titles like “Doctor shocked by this gut fix.”

Then the feed takes over.

Short videos appear in your social apps explaining “five foods that destroy your microbiome.”

Threads about adrenal fatigue and burnout show up in your recommendations.

Sponsored stool tests follow you from one platform to another.

A health influencer you’ve never seen before tells a story about being exactly where you are now and solving it with a particular protocol.

You watch one or two of these a little longer than usual. You pause on the test ad long enough to read the bullets. You click through to a supplement site, then close the tab without buying.

From your side, it feels like sampling. You looked around. You saw a landscape of options. You’re staying informed.

From the system’s side, it looks like signal.

You just told several platforms that gut-related content holds your attention more than strength-training clips or gardening videos. That you will pause for words like “root cause” and “microbiome.” That you are a warm candidate for certain kinds of products.

Tomorrow, you will see more of those.

You are no longer wandering through a neutral library. You’re walking a hallway that keeps rearranging itself around whatever you already pause for.

Two hours later, you have:

watched videos about mitochondrial dysfunction, microplastics, and EMF exposure

read threads about trauma and mast cells and polyvagal theory

clicked through supplement stacks and practitioner offers

found three new newsletters and bookmarked four podcast episodes

What has changed in your body?

In many cases, nothing.

Sleep is no closer. Dinner has not moved. The nervous system that showed up to the search, wired, tired, or both, is still sitting in the same chair, now carrying a few more open loops.

From the platform’s perspective, it was a successful evening. Creators got watch time. Brands logged ad impressions. The recommendation engine has a sharper profile of what keeps you active.

From your perspective, it feels like getting educated. You have more vocabulary than you did at the start of the night.

The only thing that might be missing is a different tomorrow.

If someone had access to your last month of health-related clicks, what confident story could they tell about you that you have not consciously chosen for yourself?

That you are “the gut protocol person”? The “adrenal fatigue person”? The “biohacker in progress”? The “autoimmune warrior”?

None of those labels are inherently wrong. The point is that they emerge from the way your attention is being steered, not necessarily from a deliberate choice about how you want your life to look.

This is already a lot.

We haven’t yet touched the part where you and I start doing this to other people.

Room Four: The Day I Took a $30,000 Loan to Learn How to Hold Your Attention

There is a point in most health journeys where you think:

“If I just knew what to do, I could help people. The problem is getting found.”

That was roughly where I was when I signed a contract and took out a $30,000 loan for a year of marketing help.

At the time, I was an entry-level practitioner. A handful of private clients. Some group sessions. No large platform. No brand team. Just enough traction to feel like the work mattered and not nearly enough to make it sustainable.

The pitch from the marketing company was straightforward: they would help me get in front of the right people. They had a track record with coaches, practitioners, and small health businesses. They knew how to build funnels, write copy, and structure offers.

Technically, they were not on the bleeding edge of anything. No proprietary AI stack. No secret algorithm. This was learned marketing, refined over decades, packaged for the online health world.

I was not the only one in that cohort.

There were nutritionists, trauma coaches, breathworkers, functional practitioners, people just out of certification. A room full of earnest, early-stage helpers who had each decided the missing piece was not more knowledge about health, but more knowledge about marketing.

What we were taught, boiled down, was not biochemistry. It was persuasion.

How to open an email so you keep reading.

How to tell a story so you feel seen.

How to name a problem in a way that makes you feel a little exposed and a little hopeful at the same time.

How to write headlines that hook first and explain later.

How to pace social posts so there is always a next step.

None of this was sold as manipulation. It was framed as “communicating your value” and “helping people understand what’s possible.”

But the skill set was clear: learn to talk and type in a way that captures attention and funnels it toward a paid offer.

When you look at the most visible health figures in your feeds, this is the common denominator. Their technical training varies. Their specific approach, whether keto, plant-based, nervous-system-centric, high-intensity, or low-intensity, varies.

What rarely varies is that they are extremely good at holding attention and moving it.

This used to be reserved for the naturals, the celebrities, the lucky few. Now, persuasion techniques are being trained as a commodity.

The industry expects it. It is simply part of the job description. If you want a sustainable business, you have to either:

become an effective persuader yourself, or

hire people whose entire role is to engineer attention around your work

I was not a big company. I was a person doing one-on-one work and occasional groups. If someone like me is taking out a loan of that size to learn this craft, the surface area of persuasion in the health space is not small. It is everywhere.

And it does not just exist at “prime time,” like the TV commercials of the 1980s.

It is on your wrist when a notification buzzes with a “quick tip.”

It is on your phone between meetings, in two-minute clips that know exactly which phrases get you to stop scrolling.

It is in your email, in subject lines that promise to finally explain why you still feel off.

It is in your car as podcast intros that smoothly auto-play the next episode.

It is with you at the table, in sponsored posts you glance at while you eat.

It follows you into the bathroom.

Hundreds of micro-touches a day, all tuned to the same goal: don’t let your attention wander away before the next promised insight, next story, next step.

The people I sat next to in that program wanted to help. Many had been through their own health crises. They cared deeply about their clients.

What the experience made clear to me was not that practitioners are villains. It was that:

health is now an attention business as much as a knowledge business

the people most visible in that space are often the ones best trained at influence, not necessarily the ones best at building health

and the rest of us, practitioners and non-practitioners, are swimming in an environment where that influence is simply the water

Once you notice that, another room comes into focus: the map you rely on to find anyone at all.

Room Five: The Shrinking Map

There was a phase, not that long ago, when typing a health phrase into a search engine felt like unfolding a messy map.

You’d get a weird mix: hospital pages, academic articles, personal blogs, forum threads, some junk, some gems. If you were persistent, you could often find independent voices, long-form stories, and obscure but useful resources.

Search actually behaved like a rough index to the web.

Over time, the experience changed.

Product searches started showing more “review” sites that turned out to be affiliate link farms.

Informational searches started surfacing big commercial health portals and content mills. The same handful of domains appeared at the top again and again.

Now we are entering a phase where you often don’t see websites at all.

You see an AI-generated summary box at the top of the page, sometimes with recommended products embedded inside it, sitting above everything else. You see ads that look almost like results. You see “people also ask” answer snippets that scrape a sentence or two from someone’s work without requiring you to click through.

Try typing something like “best probiotic for bloating” today. The first screen is likely a string of ads and “Top 10” comparison pages, most of them written to sell you something, not to help you understand anything. Actual clinicians, independent stool-testing labs, or long-form case studies sit pages down, effectively invisible unless you already know their names.

Underneath that layer, the old messy web is still there. Independent writers, careful explanations, niche forums, practitioners who don’t play the content game.

They are simply harder to find.

Platforms started out serving users: “Ask a question, get a reasonably direct answer.”

Then they shifted to serving paying customers: “Ask a question, we’ll show you what someone is paying for you to see.”

Now they are increasingly serving themselves: “Regardless of what you asked, we will keep you inside our AI box, our ad real estate, our ecosystem as long as possible.”

If you can’t find something anymore, it might not be because it doesn’t exist. It might be because it does not monetize well enough to reach the surface.

For a person trying to navigate their own health, this means the discovery tools in front of you, the places you turn first, are experiencing their own kind of chronic illness.

The map is inflamed.

You still can use it. It’s just running with perverse incentives. It no longer has your interests as its first priority.

Which brings us to the newest layer.

Room Six: The Synthetic Crowd

Until recently, you could at least assume that most of the content you encountered was created by a human on the other end of a keyboard or camera.

That assumption is no longer safe.

Just three weeks ago, I attended a three-day workshop to dig deeper into the life of an “AI Generalist.” Ten hours a day, building an AI toolkit, learning to produce content that would have taken a team of specialists a decade ago. By the end, our group had assembled a spec commercial for a Coca-Cola and Lego partnership that looked genuinely professional. The production quality was startling.

But the moment that stuck with me came when the workshop founder walked us through his own social media presence. Millions of followers. Hundreds, maybe thousands of posts. Images, videos, talking-head clips. Every one of them looked polished, natural, like a real person documenting a real life.

Not one of them was real.

I consider myself reasonably good at spotting AI-generated content. The uncanny valley of fake faces, the telltale smoothness, the slightly wrong hands. None of those flags appeared. Every post passed what I’d call my personal Turing test. If I’d encountered his feed in the wild, I would have assumed I was watching a human being share his actual life.

Now multiply that by everyone learning these same tools.

There are already AI-run accounts pushing out dozens of health and wellness videos daily. Deepfake clips of real doctors have appeared, selling supplements with faces and voices that belong to actual physicians who never endorsed anything. Campaigns can generate hundreds of slightly different versions of a single persuasive message, each tuned to a different emotional angle, so that one idea arrives looking like a chorus of independent agreement.

On forums and comment sections, moderators now routinely flag posts that feel AI-written: smooth, generic, a little too eager with perfectly packaged advice. When a significant fraction of the room is synthetic, it becomes harder to tell whether you’re in a conversation or reading an automated script.

This matters because so much of health is socially mediated. We lean on other people when we’re trying to figure out if a symptom is common or alarming, whether a treatment is worth trying, whether a practitioner is trustworthy. We look for stories that sound enough like ours to give us hope.

If the room is partly synthetic, those reality checks weaken. “A lot of people are saying this” might be one campaign with a good prompt.

I want to be clear about something: this essay is not an argument against using these tools. In fact, I make it a point to use them. The question is not whether we use AI, but whether we use it in ways that make us more ourselves or in ways that outsource ourselves. Whether the tools bring us back to what’s real or help us perform a version of reality that never existed.

The workshop founder had built something impressive. He’d also built a feed where nothing was real. Both of those facts can sit in the same room.

The question for the rest of us is which version we’re building, and which version we’re consuming without knowing it.

Room Seven: The Part of Us That Keeps Opting In

It would be easy to stop here and point at devices, platforms, influencers, and AI.

The truth is less comfortable.

The environment only works because you and I cooperate with it.

I have paid for tests I did not strictly need because waiting six months to see what happened felt unbearable.

I have bought courses I skimmed for “the one missing piece” while ignoring basic practices I already knew helped.

I have opened apps under the banner of “tracking” when the more honest label would have been “self-soothing.”

You might recognize your own versions.

Signing up for another program before really living the last one.

Scrolling “nervous system regulation tips” at midnight instead of giving your actual nervous system darkness and sleep.

Telling yourself you’re “staying informed” while your daily routines shift less than your reading list.

These moves are understandable. They are predictable in a world that offers quick hits of certainty on tap. They are also things we do.

At some point, it becomes useful to notice that they are moves, not fate, not personality traits, but behaviors repeated until they feel structural.

When I recognized how much of my own behavior fit this pattern, it became hard to claim I was only acted on by the health attention economy. I was also using it to avoid sitting in the blank space of not yet knowing what to do.

Once you see that, the question shifts.

It is no longer just, “Is this information accurate?” or “Are these platforms ethical?”

It becomes, “Who, in practice, gets to say what my sensations mean?”

Right now, many lives are arranged so that the first interpreters of your body are:

a metric

a feed

a voice trained in persuasion

an AI system tuned for engagement

and your own well-worn habits of reaching for all of the above

If you want that to change, you don’t have to fix the entire system.

You have to start changing how you allocate your attention inside it.

That is the part only you can do.

The rest of this essay is about that.

What’s Actually at Stake

It is easy to frame this as a time or distraction problem.

Scroll less, go outside more. Use fewer apps. Read real books.

All of that can help. None of it is the core issue.

What’s really at stake is the interpretive layer between your body and the world.

Every day, your nervous system is taking in:

heart rate

breathing pattern

pain

tension

ease

sleepiness

hunger

flashes of dread or relief

Those signals arrive first.

Then something has to assign them meaning.

“Heart racing” could mean: I drank too much coffee, I’m excited about this conversation, I’m inflamed, I’m about to get sick, I’m in a room that feels unsafe.

“Exhaustion” could mean: I need iron, I need rest, I need to stop pretending this job fits, I’m fighting an infection.

You cannot sense your way to a diagnosis. But you also cannot outsource all interpretation without losing something essential.

The health attention economy inserts more and more layers between signal and meaning.

Numbers. Narratives. Protocols. AI summaries. Hot takes. Funnels. Degraded search maps. Synthetic crowds.

If every sensation is immediately handed off to one of those layers for explanation, the part of you that learns from direct experience atrophies.

The goal here is not to rip out those layers. It is to put them back in their place.

To do that, you need experiments that return the interpretive layer to you, even in small ways.

Here are three.

They are not rules. They are tests you can run if you want to see your own pattern more clearly.

Experiment One: The One-Sentence Gate

For a week, before you open any health-related app, video, or article, pause long enough to answer this in one sentence:

“What problem in my actual life am I trying to solve right now?”

Not “what topic am I curious about.”

Not “what’s important in general.”

Something specific.

“I wake up at 3 a.m. and can’t go back to sleep.”

“My joints hurt climbing stairs.”

“I can’t get through a day of work without feeling wrecked by 3 p.m.”

“I want bowel movements that don’t feel like a negotiation.”

When I started doing this, I noticed that many of my impulses to check things were not tied to clear problems. They were tied to a vague sense of being behind, out of control, or not doing enough.

Those feelings are real. They are just not solvable by stuffing more input into the same hour.

If you try this gate for a few days, you may see:

moments where a clear, concrete problem emerges (good, now you have something to aim at)

moments where the honest answer is “I’m just uncomfortable not checking anything” (also useful to see)

In both cases, you’re putting your own question back at the center before handing it to anyone else.

That alone changes the quality of the answers you’re willing to accept.

Experiment Two: Seven Days Without Health Feeds

This one is simple and unpleasant in ways that tell you a lot.

For seven days:

no health reels or shorts

no new health podcasts

no new newsletters or essays about protocols or hacks

Keep whatever treatments and routines you already use. Don’t overhaul anything.

Instead, once or twice a day, jot down a few notes:

roughly how long you slept

any notable pain or symptoms

mood and energy in a sentence

a quick sketch of what you ate

This isn’t about building a perfect spreadsheet. It’s about giving your nervous system a week where the primary feedback loop is between your actions and your body, not between your fear and someone else’s content.

When I’ve done versions of this, the withdrawal is telling.

There’s often an itch around the same times of day I used to “just check something.” A sense that I’m missing out on important information. Boredom.

The itch, that’s the point. Surface it. Learn from it.

On the other side of that itch, patterns start to appear.

Certain foods that always precede certain symptoms. Certain kinds of days that reliably crush sleep. Early signs of overload that used to disappear into the noise.

At the end of the week, you can ask yourself:

“What did I actually learn from my own body this week, and how does it compare to what I usually get from the same amount of time with feeds?”

You might still choose to return to your usual input. But if you do, you’ll be walking back in with your eyes open.

Experiment Three: One Voice, One Change, Four Weeks

The health attention ecosystem encourages constant sampling.

A little of this practitioner, a little of that podcast, a thread here, a protocol there.

It feels diversified. In practice, it often means no single change gets lived long enough to produce clear feedback.

If you want to test what happens when you reverse that, try this:

Choose one source you respect.

A practitioner whose approach makes sense to you.

A book you’ve actually finished.

An essay series that holds up when you re-read it.

From that source, extract one concrete change that feels doable for four weeks.

earlier bedtimes

removing a category of food

a small, specific breathing practice

a change in when you schedule demanding work

Commit to that one change for four weeks. No stacking new protocols on top. No switching because you saw a more exciting idea on day ten.

This is harder than it sounds. Boredom shows up. Doubt shows up. Other ideas try to cut the line.

If you stay with it, something valuable happens: you get signal.

At the end of that period, you will not need anyone else to tell you whether that change mattered. Your own sleep, pain, energy, mood, or digestion will have opinions.

You may keep the change, tweak it, or drop it entirely. Any of those is fine. What matters is that the verdict came from your life, not from a comment section.

The point is not to find the final, perfect method. It is to prove to yourself that your own nervous system and daily experience are capable of delivering a clear “yes,” “no,” or “not worth it.”

That capacity is what the health attention economy cannot sell you.

A Different Way to Measure Progress

The environment we live in nudges us toward a certain metric of progress:

How much do you know?

How many experts do you follow?

How optimized is your stack?

How advanced are your biomarkers?

There is another metric available.

How often can you decide what to do next without first checking a device, a feed, or an expert?

If you felt like tracking anything for a month, you could simply notice:

how quickly you catch early signs that you are tired, overstimulated, or underfed

how simple your first response can be

how rarely you need external reassurance that this response is valid

Tools still have their place. Reading still matters. Consulting people who know things you don’t is sometimes exactly right.

The difference is the order.

First, you. Then them.

The Half-Second That Still Belongs to You

We’ve walked through a lot of rooms.

Devices and scores. Experts and conflicting narratives. Feeds tuned to your fears. A marketing culture that trains helpers to be professional persuaders. A search map that is slowly being paved over with ads and AI. Synthetic crowds. Our own well-rehearsed habits of cooperating with all of it.

None of these are going away next week.

You are not going to rebuild the internet from your kitchen.

But there is a place you still control, and it is not theoretical.

It is the half-second before you hand your attention to the system.

The moment between the buzz on your wrist and the decision to flip your phone.

The moment between the uneasy feeling and the decision to type it into a search bar.

The moment between seeing a familiar influencer’s face and deciding whether to lean in or close the app.

The moment between thinking “maybe I should check something” and asking, “what problem am I actually trying to solve right now?”

In those small pauses, no algorithm can predict you yet.

They are not noble. They are not dramatic. They are just the places where you decide whether your body’s signals get heard before everyone else weighs in.

If you practice noticing those half-seconds, even a few times a day, you are already doing something the health attention economy cannot easily monetize.

You are making yourself harder to use and easier to trust.

That may not look like much from the outside.

From the inside, it is the difference between being a data point in someone else’s business model and being the person who gets to say what your own experience means.